Grand Central Publishing

We may receive an affiliate commission from anything you buy from this article.

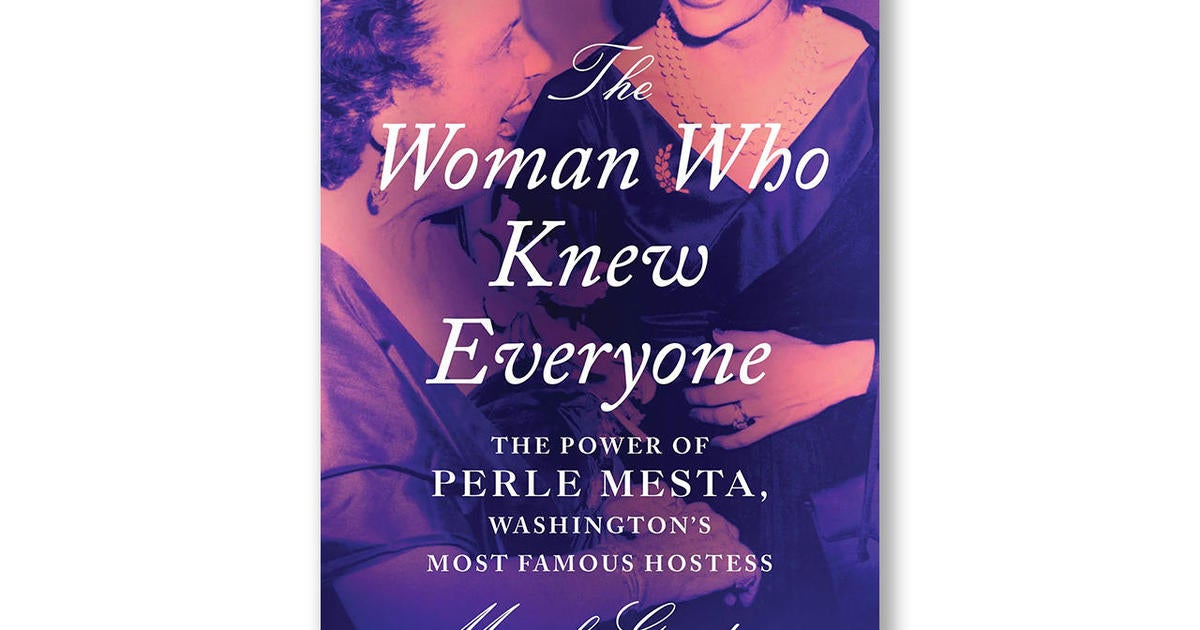

Bestselling author Meryl Gordon’s biography “The Woman Who Knew Everyone: The Power of Perle Mesta, Washington’s Most Famous Hostess” (Grand Central Publishing), tells the story of the socialite, political savant, and United States envoy to Luxembourg, who turned her gift for hosting parties in the nation’s capital into a unique form of activism, becoming one of the most famous women in America.

Mesta’s affinity for hosting politicians and celebrities would inspire a musical starring Ethel Merman, “Call Me Madam,” and a sobriquet that she was “The Hostess with the Mostes’ on the Ball.”

Read an excerpt below from Mesta’s time as Ambassador to Luxembourg, and don’t miss Erin Moriarty’s interview with author Meryl Gordon on “CBS Sunday Morning” January 19!

“The Woman Who Knew Everyone: The Power of Perle Mesta, Washington’s Most Famous Hostess”

Prefer to listen? Audible has a 30-day free trial available right now.

Perle visited overflowing orphanages populated by children whose parents died in the war. It made her heartsick. If there was ever a reason for a brighten-the-day party, this was it. On St. Nicholas Day, Perle hosted 350 war orphans, feeding them hot chocolate, sandwiches, and cookies. Perle imported a Paris puppet show and showered the children with dolls and toys. Describing her plans in a letter to Elise Morrow, Perle wrote, “Of course, I will get more fun out of this than the children will.”

A photo of the party shows Perle raptly watching the puppet show with the children, a benign smile on her face, dolls covering her lap. Even though she was recovering from the flu, she gave a speech in mangled Luxembourgish. The giggling children, who responded in English, called her “auntie.” Perle acted out of emotion rather than calculation, but this gesture—which she made into a yearly event— was a brilliant way to endear herself to Luxembourg citizens.

One young boy stood out: the child of a wartime fling between a Black American serviceman and a local woman, who died shortly after giving birth. Perle was contacted by a Washington couple who had heard about the boy and wanted to adopt him but couldn’t untangle the red tape. Concerned that six-year-old Frank would feel like an outcast in overwhelmingly white Luxembourg, Perle finessed the paperwork on behalf of Army lieutenant colonel Bert Cumby and his wife. Before the Black couple met Frank, they asked Perle for her frank opinion of the youngster. “The cutest child you ever saw,” she told them. “And I’ll say this to you. If you don’t take the child, I will.” Chance inspired Perle to take on the cause that became her most memorable innovation. Three off-duty American GIs showed up at the legation: one soldier bet the others a bottle of champagne they could meet the new minister without an official invitation. Perle not only greeted them but invited them to dinner that night with the legation’s employees. “Those three G.I.’s were the life of the party,” she later wrote. “One of them played the piano and another sang.”

After Marguerite mentioned that one soldier admitted to being homesick, Perle impulsively announced that she would hold an open house for American soldiers on the first Saturday of every month, starting on January 7, 1950. She chatted up the roughly thirty soldiers who attended the first weekend and then sent notes to their parents, telling them how much she enjoyed meeting their sons. As word spread, hundreds began to turn up from Germany and Belgium.

“I put as much thought and work into those parties as I do for a party for any senator,” she told the Associated Press. “The boys get their pay at the first of the month. They don’t have much to do. This gives them some place to go. The boys get all they want to eat, plus milk, soft drinks and champagne if they want it.”

Paul Colbert, a serviceman from Somerville, Massachusetts, fondly remembered these parties. “Perle would entertain as many as 1,200 of us at one time. She’d also write hundreds of letters home, telling our mothers she’d seen us and that we were looking fine. She’s really a wonderful person, take it from me.”

A senator wrote to the State Department demanding to know who was financing this extravagance. It certainly wasn’t the American taxpayer. Perle was underwriting it and finally had to rent a hall to accommodate the troops. She would later estimate that more than 25,000 GIs came to the Saturday night frolics. Perle delegated the details to Garner Camper, the butler she had brought over from Washington. Perle’s niece Betty, then living in Luxembourg, recalled, “He absolutely shone at these parties and all the GI’s loved him. He served steaks and barbequed ribs, cheeseburgers, and hot dogs. Garner set up a soda fountain bar and he made them ice cream sundaes and milk shakes. Perle always got a lively local band to supply the music.” In an era marked by bitter racial prejudice in America, Perle danced with any GI who asked, regardless of rank, ethnicity, or race.

Hearst columnist Westbrook Pegler, a pugnacious right-winger who visited her in Luxembourg, wrote approvingly, “Perle said she had danced with many GIs including Negroes, explaining that, although this had not been her custom in Oklahoma where she spent much of her girlhood, she thought she was representing all the people of the United States.”

* * * *

In March 1950, Perle visited war-ravaged Germany. Newspapers ran a haunting photograph of her at a displaced persons’ camp near Frankfurt hugging two Polish children. Children in the background looked hollow-eyed and lost, unable to meet her gaze.

In Heidelberg, where Perle was the first senior American diplomat to visit the city since the end of World War II, she delivered a rousing feminist speech at a local university, offering the young women hope for careers and a life different from the ones their mothers had led. She claimed, disingenuously, that America had abolished the “petticoat line,” which she defined as a societal restriction “which once kept America’s women spending her day over a hot stove in a smoky kitchen while her husband basked in the sunshine of public life.”

In a bout of optimism, she declared, “Unlike the members of her sex in some other lands, where women still plow the fields and carry heavy loads on their backs, the woman of America has achieved a place of her own in the public scene—right alongside the man.”

Perle, at least, had done it, achieving her place in the public sphere whether the men in the American diplomatic corps liked it or not.

Excerpted from “The Woman Who Knew Everyone: The Power of Perle Mesta, Washington’s Most Famous Hostess” by Meryl Gordon. Copyright © 2025 by Meryl Gordon. Reprinted by permission of Grand Central Publishing, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc., New York, NY. All rights reserved.

Get the book here:

“The Woman Who Knew Everyone: The Power of Perle Mesta, Washington’s Most Famous Hostess”

Buy locally from Bookshop.org

For more info:

-

“The Woman Who Knew Everyone: The Power of Perle Mesta, Washington’s Most Famous Hostess” by Meryl Gordon (Grand Central Publishing), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats