Impact of toxic ash from L.A. wildfires on oceans

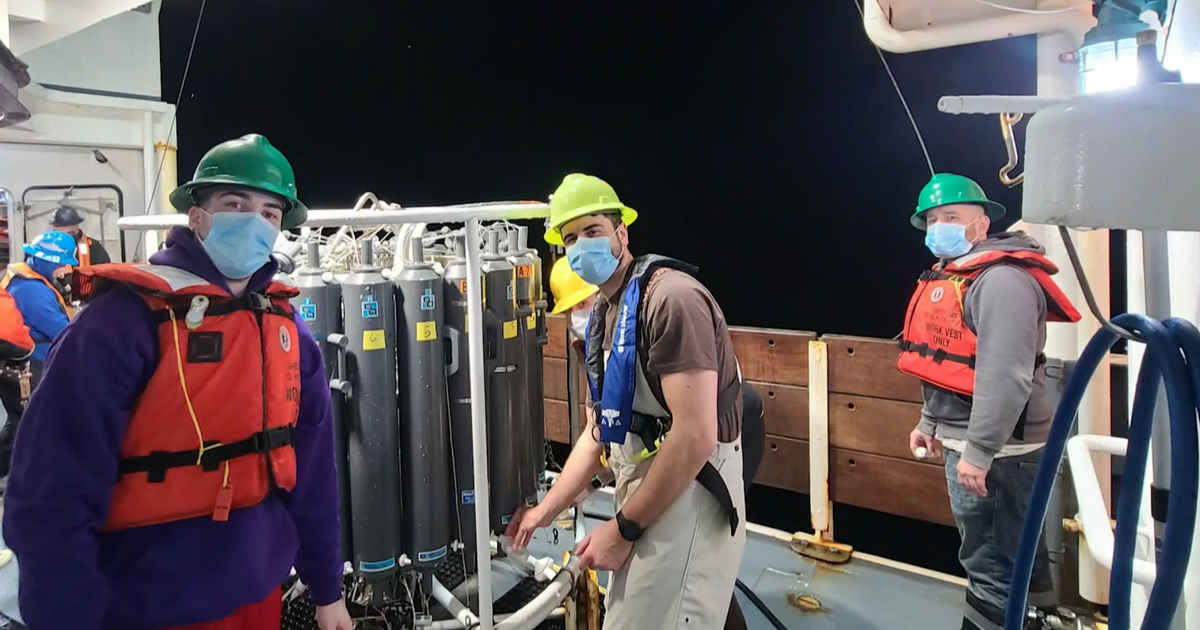

Los Angeles — A research ship from the San Diego-based Scripps Institute of Oceanography goes out every three months along the Southern California coastline.

Recently, the ship was traveling the coast collecting plankton samples, small organisms that many larger fish live on. But this trip was anything but ordinary.

“This is something I’ve never experienced before, and I don’t know anybody else that has,” Scripps Institute scientist Dr. Rasmus Swalethorp told CBS News.

What the researchers experienced, by total coincidence, was pulling up to Los Angeles in January as the deadly and devastating Palisades and Eaton fires were burning thousands of homes, incinerating plastic, paint, asbestos and car batteries. The fires released a cloud of toxic ash that settled over the ocean for about 100 miles.

Crew members put on masks to protect against the smoke as black ash settled on the ship, while the plankton they collected was also swimming in ash.

“All the organisms that are going to live down on the seabed, they’re certainly going to be exposed to this, potentially transporting whatever is in that ash further up the food chain,” Swalethorp said.

Scientists with the Scripps Institute have been collecting California ocean samples for 75 years. The new ash-laden samples will be added to this vast archive.

“We know what the fish are like under normal circumstances, but the scientific opportunity here is to look at the condition of the fish when they’re exposed to all the ash,” said Andrew Thompson, a scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Commercial and recreational fishing in California brings in about $1 billion a year and supports 193,000 full and part-time jobs, according to numbers from the NOAA. While it could take years to know how, or if, these toxins impact fish, both fishermen and restaurants say knowing the answer is important.

“The damage that these fires has caused is like woven so deeply into the fabric of our food systems that it’s something that you know, it should be just an absolute red flag for anyone involved…a red flag for change,” said Michael Cimarusti, a chef at the L.A. seafood restaurant Providence. “Like, what can be done to ensure that these kinds of fires, like, don’t happen again.”

Swalethorp says monitoring how ocean life responds will continue for years.

“We are also going to be looking for chromium, for mercury,” Swalethorp said. “…Things we don’t want in the ocean.”

But because of a grim kind of luck, scientists at least have a head start in knowing exactly what toxins they are looking for.